Design thinking has become something of a buzzword in recent years. But behind the buzz is a genuinely transformative way of approaching problems one that centers on people. This framework, known as Human-Centered Design (HCD), is about more than just solving problems; it’s about solving the right problems. And the key lies in deeply understanding human needs, cultures, and contexts.

I recently attended a Masterclass on design thinking, and it left me reflecting on how powerful this approach can be—not just for businesses but for anyone grappling with complex challenges. The insights I walked away with underscored how HCD has evolved, why it matters, and how its principles can be applied effectively. But before we jump into that - let me share Steve Job's thought how merging humanities with sciences was the key to apple's success.

Steve jobs on Apple experiences:

"There were a lot of people at Apple that just didn't get it. We fought tooth and nail with a variety of people there who thought the whole concept of a graphical user interface was crazy ... on the grounds that it couldn't be done, or on the grounds that real computer users didn't need menus in plain English, and real computer users didn't care about putting nice little pictures on the screen. But fortunately, I was the largest stockholder and the chairman of the company, so I won. Apple was a corporation, we were very conscious of that. We were driven to make money. I would say that Apple was a corporate lifestyle, but it had a few big differences from other corporate lifestyles I'd seen. The first one was a real belief that there wasn't a hierarchy of ideas that mapped into the hierarchy of the organization. In other words: great ideas could come from anywhere. Apple was a very bottom-up company when it came to a lot of its great ideas. We hired truly great people and gave them the room to do great work. A lot of companies — I know it sounds crazy — but a lot of companies don't do that. They hire people to tell them what to do. We hire people to tell us what to do. We figure we're paying them all this money; their job is to figure out what to do and tell us. That led to a very different corporate culture, and one that's really much more collegial than hierarchical. I think our major contribution [to computing] was in bringing a liberal arts point of view to the use of computers. If you really look at the ease of use of the Macintosh, the driving motivation behind that was to bring not only ease of use to people — so that many, many more people could use computers for nontraditional things at that time — but it was to bring beautiful fonts and typography to people, it was to bring graphics to people ... so that they could see beautiful photographs, or pictures, or artwork, et cetera ... to help them communicate. ... Our goal was to bring a liberal arts perspective and a liberal arts audience to what had traditionally been a very geeky technology and a very geeky audience. In my perspective ... science and computer science is a liberal art, it's something everyone should know how to use, at least, and harness in their life. It's not something that should be relegated to 5 percent of the population over in the corner. It's something that everybody should be exposed to and everyone should have mastery of to some extent, and that's how we viewed computation and these computation devices.”

“I think great artists and great engineers are similar, in that they both have a desire to express themselves. In fact some of the best people working on the original Mac were poets and musicians on the side.”

HCD isn’t a new idea. Its roots stretch back to the early 20th century, when industrial designers began thinking about ergonomics and usability. But it wasn’t until the cognitive revolution of the 1960s that the field really began to take shape. The rise of personal computing in the 1970s and 80s brought usability to the forefront, and by the early 2000s, companies like IDEO had popularized design thinking as a framework for tackling not just digital challenges but broader organizational ones.

Today, the scope of HCD has expanded further. Inclusive design is now a major focus, emphasizing the need to consider diverse users and contexts. It’s no longer just about making things work—it’s about making them work for everyone. One of the most compelling ideas from the Masterclass was that HCD isn’t just about designing solutions. It’s about designing solutions that matter. To do this, you have to start by understanding the people you’re designing for—their needs, limitations, and goals.

This focus on people has a real impact. A striking statistic shared during the session highlighted that companies integrating design thinking into their strategy can outperform industry peers by as much as 228%. But the benefits go beyond revenue. Seventy-one percent of companies reported that design thinking improved their working culture, leading to greater productivity and employee engagement.

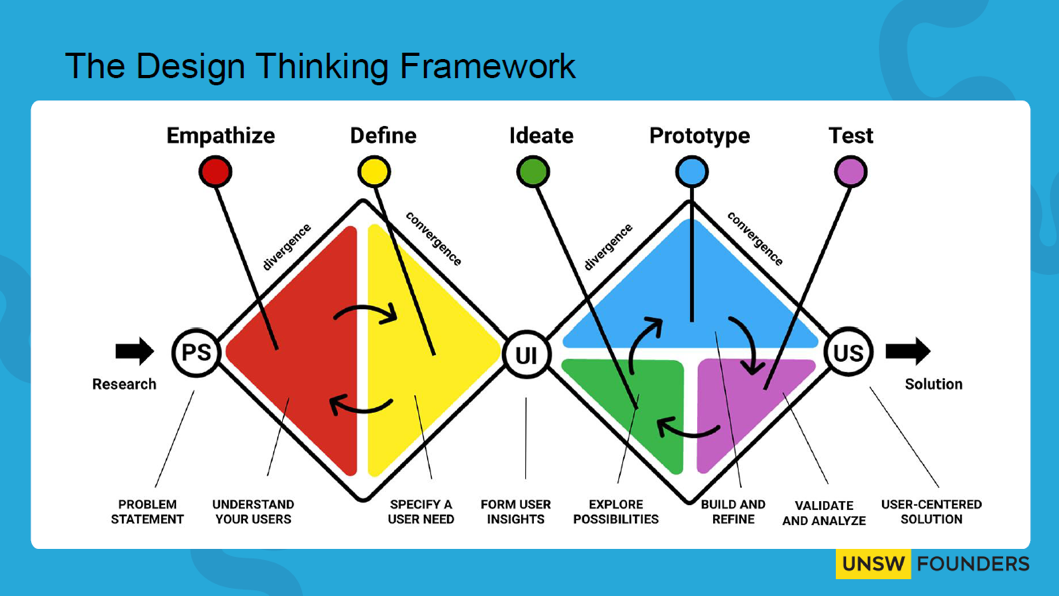

At the heart of design thinking lies the Double Diamond Framework, a simple yet profound way of visualizing the design process. It’s divided into four phases, alternating between divergent and convergent thinking:

- Discover: This is where you explore the problem space, gathering insights into users’ needs and challenges. It’s about asking questions, not rushing to answers.

- Define: Once you’ve gathered enough data, the focus shifts to clarity. What’s the real problem? This step sets the stage for everything that follows.

- Develop: With a clear problem in mind, it’s time to brainstorm solutions. This is the phase for creativity, experimentation, and pushing boundaries.

- Deliver: Finally, you narrow down and refine your solutions, creating prototypes, testing them, and iterating until you arrive at something ready to launch.

The beauty of this framework lies in its structure. It provides a clear path forward, but it’s flexible enough to adapt to the messy, iterative nature of real-world problem-solving. The Masterclass also introduced a range of tools that can be used throughout the design process. Here are a few that stood out:

- Empathy Mapping: This tool helps teams step into users’ shoes by exploring their thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Journey Mapping: By visualizing the user’s experience across different touchpoints, you can identify pain points and opportunities for improvement.

- Rapid Prototyping: Quickly building and testing ideas allows for fast feedback and iteration.

- User Interviews: Structured conversations with users provide invaluable insights into their needs and preferences.

Each of these tools reinforces the idea that good design starts with good listening.

One of the most important lessons from the Masterclass was the distinction between problem explorers and problem solvers. Too often, we rush to solutions without fully understanding the problem. This leads to what’s known as “designer myopia,” where solutions may impress peers but fail to meet users’ actual needs.

The design thinking framework forces you to slow down and explore. It emphasizes that the most innovative solutions often emerge from a deep understanding of the problem space. And that understanding doesn’t come from sitting in a conference room—it comes from engaging with real people in real contexts.

Ultimately, HCD isn’t just about creating functional solutions. It’s about creating solutions that resonate—solutions that are meaningful, sustainable, and deeply human. The structured yet flexible nature of the Double Diamond Framework makes it an invaluable tool for navigating uncertainty, exploring diverse ideas, and delivering outcomes that matter.

The real power of design thinking lies in its ability to align creativity with purpose. By centering on human needs and encouraging collaboration across disciplines, it transforms not just what we create but how we create. And in doing so, it opens the door to solutions that truly make a difference. Design thinking isn’t just a process; it’s a mindset. It’s about curiosity, empathy, and the willingness to embrace complexity. The lessons from the Masterclass reinforced the idea that by staying grounded in human-centered principles, we can tackle even the most challenging problems with confidence and creativity.